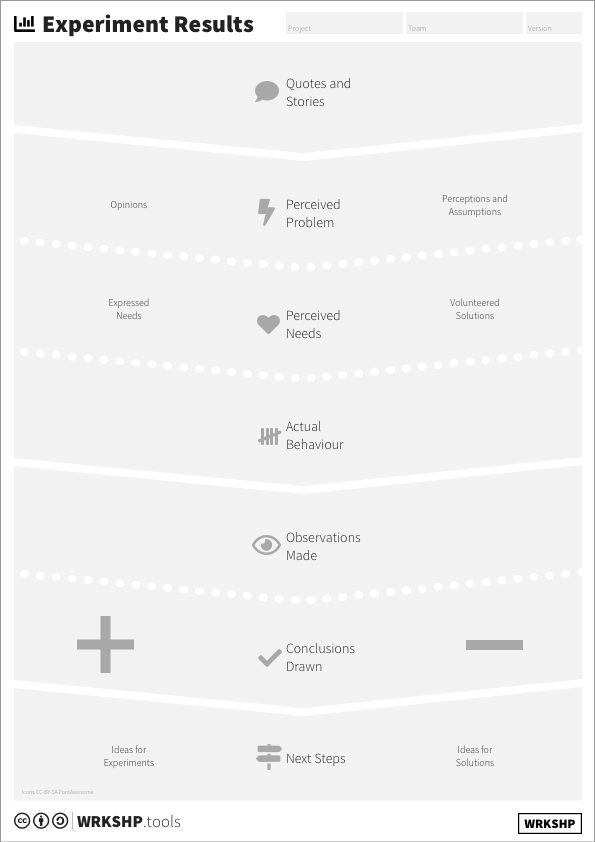

Experiment Results Canvas

The Experiment Results Canvas helps you to make sense of the outcomes of a qualitative experiment in a workshop setting.

Use this tool when:

- you want to make sense of (qualitative) experiment results in a workshop setting

Overview

| Time | ± 45 minutes | |

| Difficulty | 3 / 5 | |

| People | 3 - 5 | |

| Author | erik van der pluijm | |

| Website | ||

| License | CC BY SA 4.0 |

What is it and when should I use it?

As a startup founder, the Lean Startup methodology tells you that you should be running experiments all the time. You should be out validating your idea, problem-solution fit, and product market fit.

In theory, this makes total sense. In practice, however, it can be quite difficult to make sense of the results of your experiments. Especially in the early stages, when you are running qualitative experiments, it is hard. First of all, you need a way to collect and share the information you received with your team. And, even more important, how are you going to draw conclusions from the results?

People tend to focus on the interviews they have conducted themselves. They notice the things that they already agree with, or have noticed before. This leads to a strong confirmation bias. The method you use should be able to deal with this.

Initial interviews are necessarily exploratory in nature. At this point, the team can’t really know in detail what they are looking for. There won’t always be a clear script to follow, and the answers are varied.

You simply can’t follow the approach that would be used for a large scale survey and use statistics. The low number of responses and the unstructured nature of the results make that impossible. This makes it very difficult to make a clear ‘validated or invalidated’ decision.

From a statistical point of view your results are a complete waste of time. But at the same time, they are a treasure trove of information about your customers.

How to fix it?

So, what can be done? How can we explore qualitative interview results in a workshop setting in a meaningful way? A way that is as objective as possible? How can we extract as much useful information from the interviews as possible?

- Homework: First, going over the results in detail is required. That takes more time than you generally have in a workshop. So, first of all, homework is required. Doing time-consuming and sometimes expensive interviews and then avoiding to dive into the results is a total waste. If the team is prepared to interview 10 people, then they should also be prepared to read all the results before going into the workshop. Only looking at your own results means you’ll open the door to extra confirmation bias.

- Framework: Second, a framework is needed to organize the results. The Experiment Result Canvas below was created as one (highly effective) way of doing that.

Tool Overview

Quotes and Stories Actual quotes, answers and stories your respondents gave you.

Perceived problem How respondents experience the problem you want to solve.

Perceived needs What respondents tell you about what they think they need.

Behaviour What respondents have already done in the past to deal with the problem.

Your observations What observations were made by the interviewer?

Your conclusions What conclusions did they draw?

Next steps What follow up questions would you like to ask? What other things would you like to know?

Steps

1 Quotes and stories

The first category is filled with raw quotes and stories selected from interviews.

2 Perceived problem, perceived needs, and behaviour

The second category splits results in information about the respondent’s perceived problem (how they experience the problem you want to solve), their perceived needs (what they tell you about what they think they need), and their actual behaviour (what they have already done in the past to deal with the problem).

This distinction is important, because it is so easy to pick up only on what you’d like the respondent to answer to your question. It’s so easy to hear that they like your solution, or that they really need it. But that information is close to worthless. (They’re probably lying — or being polite).

Solutions and opinions volunteered by respondents, telling you how they might solve the problem in the future, are also close to worthless information. People don’t know what they will or won’t do in the future, and they have a very difficult time predicting their own feelings.

The thing to look for is behaviour. Have they actually experienced the problem in the past, and did it bother them enough that they actually found or tried to find a solution for it? That is what you need to hear if you’re looking for information coming from early interviews. It’s much harder to ‘be polite’ about actual behaviour. It’s the actions that count, not the words and opinions.

Sticking this information in separate boxes means it is all there, but it’s organized in an ‘evidence pecking order’. The behaviour box is the most important one. But, if a lot of people say the same things, or have the same opinions, you might want to run a separate experiment based on that and see if their actions reflect those opinions.

3 Your observations and conclusions

The third category can be filled with the interviewer’s notes. What observations were made by the interviewer? What conclusions did they draw?

It is important to keep this information separate so that it won’t get mixed with the results coming from the respondents.

It’s great to collect these observations, and they may help you a lot, but they are your observations. They are something that you added — and therefore, based on what you already knew before you conducted that interview. They reflect your view of the world and your biases more than anything else.

4 Next Steps

Finally, there is space for next steps. What follow up questions would you like to ask? What other things would you like to know?

This tool can be used as a guideline to structure unstructured interview results, and to cluster results together. You can use it to prepare for the workshop and pre-process your interview results. In that way, you can use your time in the workshop to make sense of the results, and, once you have done that, vote—but in an effective way.

Now at least, if you do place your dot vote sticker next to an interesting behaviour, it’ll be clear that that is much more valuable than a vote for your own observation or opinion

You can more or less see from where the dots are on this canvas if they are more likely to be influenced by confirmation bias.

Finally, using this tool can help to compare results over time coming from different interview settings with different formats.